Dogs Who Survived the Titanic

Introduction

When the RMS Titanic struck an iceberg on April 14, 1912, and sank into the North Atlantic, over 1,500 people lost their lives in one of history’s most infamous maritime disasters. But among the loss and human tragedy, there exists a lesser-known story—one that speaks to loyalty, love, and the quiet presence of animals during catastrophe. Aboard the Titanic were at least a dozen dogs, some of whom met tragic ends, while three small dogs survived. This article recounts the fate of those canine passengers, providing a nuanced look at class divisions, emotional attachments, and the dogs who witnessed history.

Animals Aboard the RMS Titanic

The Titanic wasn’t just a floating palace for humans; it also accommodated their pets. Wealthy passengers traveling in first class often brought their beloved animals along, including birds, cats, and most notably, dogs. These pets were not simply accessories. They were cherished companions, many bred for prestige, companionship, or show. The White Star Line, which operated the Titanic, had provisions for pets, including an onboard kennel, access to deck walks, and in some cases, even the permission for animals to stay in cabins.

First-Class Privileges and Pet Companionship

Most of the documented animals on the Titanic belonged to first-class passengers. These affluent travelers had the influence and financial leverage to negotiate extra space and services for their pets. The kennel on the ship was reserved for larger breeds, while smaller dogs were occasionally allowed in private staterooms. These included toy dogs such as Pomeranians and Pekingese, which were popular among upper-class women during the Edwardian era. The privileges of first class extended beyond dining and deck access—it shaped which lives, human or animal, had the best chances of survival.

Famous Dog Breeds on the Titanic

Historical accounts mention a variety of breeds aboard the Titanic. Among them were a French Bulldog, a Fox Terrier, a Toy Poodle, an Airedale Terrier, and multiple Pomeranians and Pekingese. These breeds were popular among high society at the time, often chosen for their elegance, trainability, or fashionable appeal. The Pomeranian, for instance, had become a favorite after Queen Victoria introduced it to British aristocracy. Meanwhile, the Pekingese represented exotic luxury, as the breed had only recently been brought from China to Europe and America.

also read this Famous Historical Dogs

How Many Dogs Were on the Titanic?

Official records about animals on the Titanic are sparse, but survivor testimonies and passenger lists suggest that at least 12 dogs boarded the ship in Southampton or Cherbourg. Since White Star Line did not document pets with the same diligence as passengers, many details about these animals come from personal letters and anecdotal accounts. Notably, most of the dogs were owned by first-class travelers. Little is known about whether third-class or crew members brought pets aboard, although it is believed a few cats and possibly a working dog may have been present below deck.

The Three Dogs That Survived

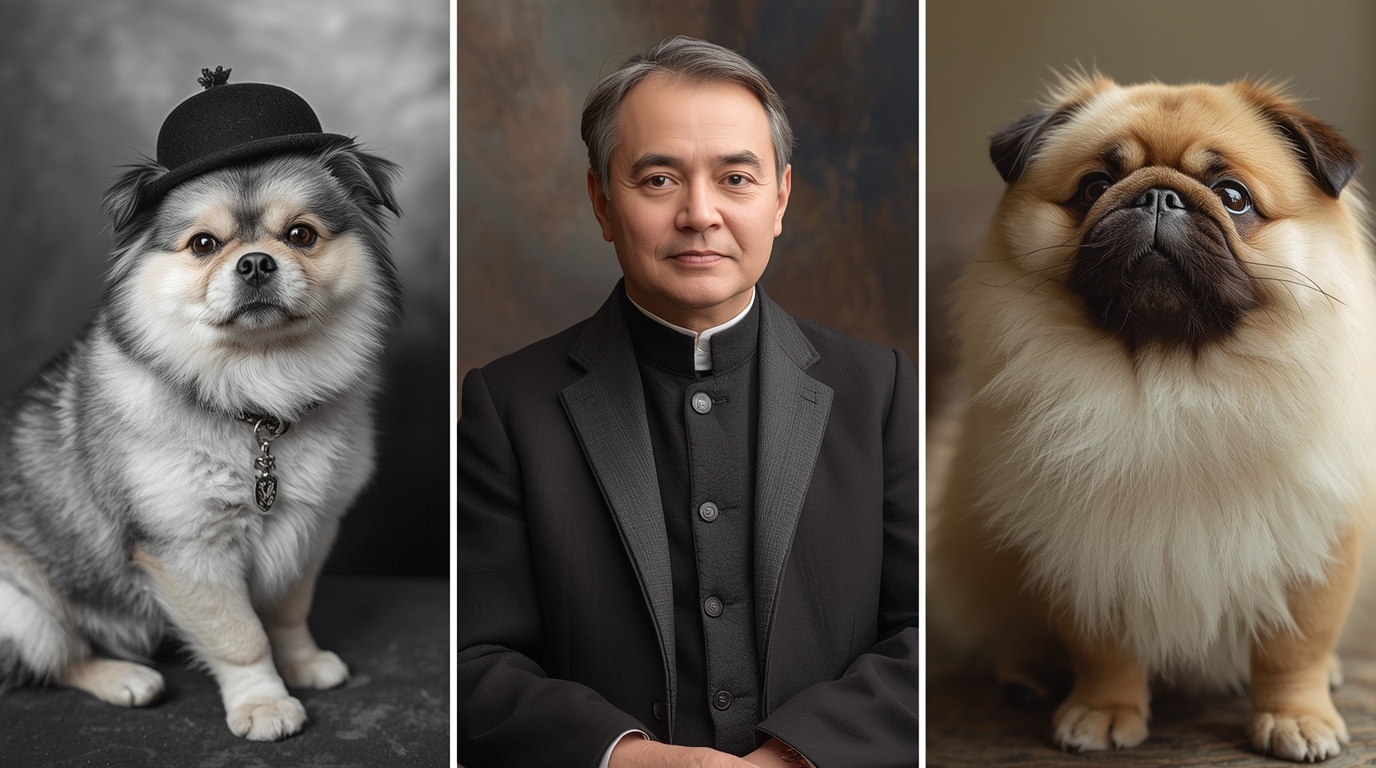

Among the known canine passengers, only three dogs survived the Titanic disaster. All three were small breeds and, crucially, allowed by their owners to remain in the cabins. This circumstance meant they could be quickly carried into lifeboats during the evacuation. The survivors included two Pomeranians and one Pekingese, each owned by first-class passengers who valued their pets enough to defy chaos and possibly risk scrutiny to bring them aboard lifeboats.

Lady: The First Pomeranian Survivor

One of the surviving dogs was a small Pomeranian named Lady, owned by American passenger Margaret Hays. A wealthy 24-year-old from New York, Hays had boarded the Titanic with friends after traveling in Europe. When the ship struck the iceberg, Hays carried Lady wrapped in a blanket to Lifeboat 7. She and her dog were rescued by the RMS Carpathia and later returned to New York.

Lady became a subtle celebrity among Titanic animals. Though she never gained the media attention of human survivors, Lady’s story was retold in several memoirs. Hays reportedly described how people on the Carpathia were charmed by the tiny dog and how Lady offered her comfort during the hours of cold uncertainty.

Sun Yat Sen: The Pekingese Survivor

The second canine survivor was a Pekingese named Sun Yat Sen, owned by Henry and Myra Harper of Harper & Brothers publishing fame. The Harpers had chosen to travel with their beloved dog in their first-class suite. When it became clear the Titanic was sinking, they brought Sun Yat Sen with them into Lifeboat 3.

Survivor accounts suggest that Sun Yat Sen was calm throughout the ordeal, sitting silently in Myra Harper’s arms as they drifted away from the sinking ship. Unlike some passengers who were questioned about bringing animals aboard lifeboats, the Harpers’ status likely helped shield them from criticism. After returning to New York, the couple remained protective of their dog, rarely speaking publicly about the experience.

The Second Pomeranian: Name Lost, Story Survives

The third dog to survive was another Pomeranian, owned by Elizabeth Rothschild. She was traveling alone in first class and refused to board Lifeboat 6 without her dog. When crew members told her that dogs were not allowed, she allegedly defied them, hiding the small dog in her coat or handbag. Though the dog’s name was not recorded in most accounts, it was confirmed in later testimonies that she brought her Pomeranian aboard and kept it with her on the Carpathia.

Rothschild’s determination likely saved her pet’s life. Her story also highlights how social class and personal resolve could influence outcomes during the Titanic’s final hours.

Why These Dogs Survived

Several factors contributed to these dogs’ survival. Most importantly, they were small enough to be concealed or carried easily during evacuation. Large dogs, confined to the kennel or left in staterooms, could not be rescued quickly or discreetly. The owners’ first-class status also played a role. In the early stages of evacuation, first-class passengers had better access to lifeboats and faced less scrutiny when making personal requests.

Moreover, the deep emotional bonds between these passengers and their pets motivated acts of defiance and compassion. In a moment when many passengers had to choose between saving their families and possessions, these individuals chose to save their animals—an act that speaks volumes about their priorities.

Dogs That Perished in the Sinking

Not all dogs aboard the Titanic were as fortunate. Among the perished were larger breeds like a Great Dane, an Airedale Terrier, and a Bulldog. These dogs, often housed in the ship’s kennel or in first-class staterooms, could not be saved due to their size, weight, or location.

One of the most poignant stories involves a dog named Frou-Frou, a toy breed owned by Helen Bishop. As the Titanic sank, Bishop attempted to carry Frou-Frou to safety, but a crew member told her there was no room for pets. She reluctantly left the dog behind. According to Bishop’s account, the dog clung to her dress as she departed, as if sensing the impending doom. That haunting image of loyalty remains one of the most emotional stories involving Titanic’s animal passengers.

The Onboard Kennel and Its Fate

The Titanic featured an official kennel on F Deck, near the ship’s cargo hold. Here, larger dogs were housed, exercised daily by crew members, and fed according to instructions from their owners. Some passengers even held informal “dog shows” on deck, showcasing their purebred companions.

When the iceberg struck, no formal plan was in place to rescue the kennel dogs. Confined far below the main decks, they were among the first to be impacted by flooding. Several accounts suggest that the kennel was unlocked near the end, possibly on orders from Captain Smith or compassionate crew. While this act may have freed the dogs, it also meant they ran frantically through the tilting decks, disoriented and doomed.

The Tragic Loyalty of Frou-Frou

Frou-Frou’s story is particularly heartbreaking because of the emotional depth it reveals. Helen Bishop later described how the dog “seemed to know that it was being left behind.” Frou-Frou’s efforts to hold on, refusing to let Bishop go, is emblematic of the selfless loyalty dogs show their humans—even in crisis.

No photographs of Frou-Frou survive, but the dog’s memory endures through memoirs and Titanic lore. Frou-Frou symbolizes the bond between pet and owner, and how that bond endures even in death.

Captain Smith’s Reported Affection for Dogs

Several reports suggest that Captain Edward Smith, the Titanic’s commander, had a personal affection for the ship’s animals. As a longtime White Star Line officer, Smith often allowed dogs on board and is said to have visited the kennel during transatlantic voyages.

A popular, though unverified, story claims that Captain Smith ordered the kennel dogs released as the ship sank, allowing them a chance to escape. While there’s no official record confirming this, some survivors did report seeing dogs running loose on deck in the final moments.

Human-Dog Bonds in Crisis

The presence of dogs aboard the Titanic was more than symbolic—they served as emotional lifelines. In the cold Atlantic darkness, as lifeboats drifted and hopes dimmed, survivors clung not just to each other, but to any source of comfort. For Margaret Hays and Myra Harper, their small dogs were not just survivors—they were survivors’ companions, offering warmth and reassurance during unspeakable trauma.

This phenomenon is echoed in modern disaster psychology, which recognizes that animals can reduce stress, lower anxiety, and even improve survival instincts in high-risk situations.

Controversy Around Dogs in Lifeboats

Not everyone celebrated the survival of the Titanic’s dogs. In the days following the sinking, several newspapers criticized the fact that animals had been given space on lifeboats when so many people perished. These sentiments, while understandable in their grief, overlooked the circumstances—most of the dogs that survived were tiny enough to fit in a handbag and did not displace any human.

Nonetheless, the idea of “dogs over people” became a recurring theme in Titanic sensationalism, often distorting the reality for dramatic effect.

Dogs in Titanic Folklore and Myth

As with many aspects of Titanic’s story, folklore and myth have obscured the truth about the dogs. Some tales speak of dogs barking warnings before the iceberg hit, others tell of a Newfoundland that swam between lifeboats, saving lives. While most of these stories are apocryphal, they reflect a cultural need to find loyalty and heroism even among non-human passengers.

The three dogs who survived did not perform daring rescues or barked alarms, but their simple presence offered a narrative of hope.

Reactions in Newspapers and Memoirs

Though dogs were rarely the focus of post-sinking headlines, several newspapers did mention them in passing. The New York Times and Boston Globe referenced the survival of Lady and Sun Yat Sen, usually in articles profiling their wealthy owners. In private memoirs, however, dogs played a larger emotional role—offering structure to the chaos and companionship to the lonely.

Survivors often mentioned pets as part of their trauma—remembering how they were lost, or how they offered comfort.

Titanic Museums and Dog Exhibits Today

Modern Titanic museums have embraced the role of dogs in the ship’s story. Exhibits in places like the Titanic Museum Attraction in Branson, Missouri and Pigeon Forge, Tennessee include photographs, recreated kennels, and plaques dedicated to the animals lost and saved. Visitors are often surprised to learn of the dogs’ presence, and their stories serve to humanize the broader tragedy.

Educational programs also use the dogs as entry points for discussions on class, emotion, and survival.

Lessons in Class and Compassion

The story of the Titanic’s dogs is also a story of social hierarchy. The ability to save a pet in such a crisis was often a luxury reserved for the elite. Larger dogs, owned by first-class passengers but stored below deck, were less likely to survive. Third-class passengers with pets, if any, are almost entirely undocumented.

Yet these stories also showcase compassion in crisis. The owners who saved their pets did so not out of selfishness, but out of love—and in some cases, at personal risk.

Conclusion

The sinking of the Titanic remains a human tragedy first and foremost. But in the shadows of that story are smaller narratives—of devotion, loyalty, and survival. The three dogs who survived did so because of their owners’ love, their small size, and the privileges they unknowingly benefited from. Others perished, remembered only in stories and memorials.

These dogs—Lady, Sun Yat Sen, and the unnamed Pomeranian—remind us that in the cold Atlantic night, companionship mattered, and that even in disaster, the bond between humans and dogs remained unbroken.