Dogs in South America and Inca Culture

Introduction

Dogs have been intertwined with human civilization for over 15,000 years. In South America, and particularly within Inca culture, the presence of dogs reveals a deeper narrative that spans domestication, symbolism, and sacred practice. Understanding the relationship between dogs and the Inca Empire not only uncovers their cultural role but also enriches our appreciation of the Andean worldview.

Brief Overview of the Inca Civilization

The Inca Empire, known as Tawantinsuyu, spanned a vast territory across modern-day Peru, Ecuador, Bolivia, Chile, and Argentina. Dominating the Andes from the 13th to the 16th century, the Inca were deeply spiritual and maintained a close connection to nature. Animals played a critical role—both practical and ceremonial.

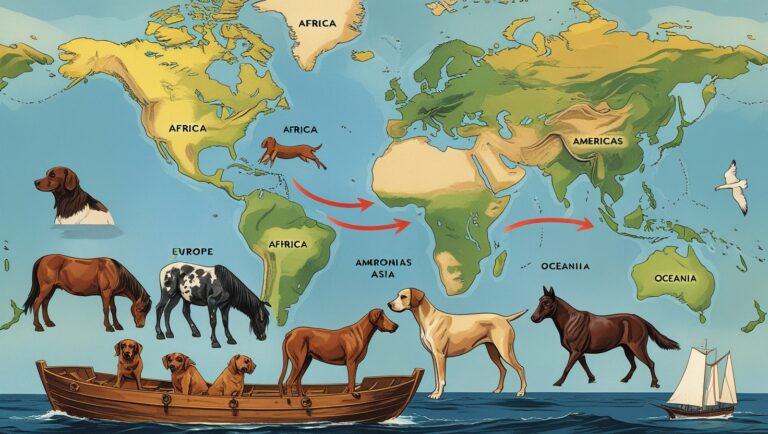

Dog Domestication in South America

Archaeological evidence from Peru, Bolivia, and Ecuador suggests that dogs were domesticated in South America as early as 5,000 years ago. Remains show small to medium-sized dogs buried alongside humans, indicating their valued status. DNA from these canines points to a local lineage separate from Eurasian breeds, suggesting independent domestication events or early migration patterns.

Notable Native Dog Breeds of South America

Peruvian Hairless Dog

An ancient breed, the Peruvian Hairless Dog has minimal hair, a slender body, and is well adapted to the Andean climate.

Chiribaya Dog

Discovered in the Moquegua Valley, the Chiribaya Dog is extinct but was well-documented through skeletal remains and burial artifacts.

Other Regional Breeds

Lesser-known regional breeds have been identified through zooarchaeological surveys, but are often under-documented.

The Peruvian Hairless Dog: Icon of National Heritage

The Peruvian Hairless Dog (Perro sin Pelo del Perú) is recognized by Peru as a national cultural heritage breed. It features prominently in pre-Columbian art, including Moche and Inca pottery. Despite a decline during colonial times, this breed has been revived through conservation efforts. Modern Peruvian households and even museums now proudly display this unique breed.

Chiribaya Dog: The Lost Breed of the South

Unearthed in 2006, the Chiribaya Dog was found buried with blankets, maize, and pottery, suggesting a ritual status. Research indicates it was short-legged, broad-headed, and resembled a terrier. Its extinction followed the Spanish conquest, likely due to crossbreeding and displacement.

Dogs in Pre-Columbian Cultures

Pre-Inca civilizations like the Moche, Nazca, and Chavin also revered dogs. Pottery depictions show dogs running, hunting, or sitting beside humans. These images reinforce the continuity between early Andean cultures and the Inca’s perspective on dogs.

Dogs in Inca Religion and Mythology

In Inca mythology, animals were often embodiments of spiritual entities. Dogs were linked with the afterlife, guiding spirits through dark pathways. They were also believed to ward off evil or act as psychopomps—souls’ escorts after death.

The Role of Dogs in Inca Society

Dogs played functional roles—guarding fields, herding llamas, and protecting homes. Their social roles, however, were equally significant. Being companions in life and partners in death, they were sometimes buried beside children or women, indicating emotional attachment.

Inca Burial Practices Involving Dogs

Tombs across Cusco, Moquegua, and Arequipa show dogs buried in ceremonial positions, wrapped in textiles or placed with offerings. Scholars debate whether these were sacrificial rituals or acts of love and kinship. Carbon dating indicates these practices peaked between 1100–1500 AD.

Canine Artifacts and Iconography

The Museo Larco in Lima and the Inka Museum in Cusco house artifacts showing dogs with human-like expressions. Textiles feature geometric patterns with canine symbols, reinforcing the dog’s role in cosmology.

Sacred Animals vs. Domestic Pets

The Inca worldview didn’t always separate the sacred from the mundane. Dogs could be livestock herders by day and ritual protectors by night. This dual identity adds complexity to interpreting burial findings and iconography.

Spanish Conquest and Cultural Disruption

The 16th-century conquest introduced European dogs—Mastiffs, Greyhounds, and Spaniels—used for warfare and intimidation. These foreign breeds often displaced native dogs, both genetically and culturally. Many native breeds declined sharply post-1550.

Survival and Decline of Indigenous Dog Breeds

By 1700, indigenous dog breeds were near extinction. Spanish chroniclers rarely mentioned native dogs. Today, only the Peruvian Hairless Dog remains officially recognized, though genetic traces of others exist in rural Andean villages.

Modern Recognition of Ancient Breeds

The Peruvian government, with backing from UNESCO, declared the Peruvian Hairless Dog a national symbol in 2001. Breed clubs, geneticists, and historians collaborate to preserve ancient DNA lines.

The Role of Dogs in Modern Andean Communities

In rural Quechua and Aymara communities, dogs still guard fields and homes. Though modern breeds like Labradors are common, native breeds retain symbolic value. Some villages continue ritual dog burials, linking past and present.

Canine Symbolism in Contemporary Peru

Dogs appear in festivals, poetry, and children’s stories. Urban artists include dogs in murals and sculptures as a nod to Inca traditions. In Cusco, dog-themed parades celebrate indigenous roots.

Archaeological Studies and Genetic Mapping

Recent studies, such as those from San Marcos University, analyze dog bones from Inca ruins using mitochondrial DNA sequencing. Findings show distinct maternal lineages, supporting the idea of isolated dog populations in pre-Hispanic Peru.

Cultural Heritage Laws and Dog Preservation

Laws enacted in 2004 and 2015 prohibit the mistreatment and genetic alteration of native breeds. Museums and NGOs offer dog-themed heritage tours, and government programs fund rural breeding efforts.

Also read this Dog History by Region

Dogs as Bridges Between Past and Present

Dogs serve as living connections to an ancient world. They offer continuity in customs, beliefs, and emotional experiences. This link has tourism and educational value, especially in archaeological parks like Pachacamac and Sacsayhuamán.

Tourism and Historical Dog Breeds

Guided tours often include stories about Inca dogs, especially in Machu Picchu, where remains were discovered in Temple of the Sun. Hotels and tourism agencies promote the Peruvian Hairless Dog as a cultural ambassador.

Popular Culture Representations

TV shows, documentaries, and even Peruvian postage stamps have featured indigenous dogs. Educational programs in schools include units on “Animals of the Inca World.”

Scientific Contributions to Understanding Inca Dogs

Institutions like Stanford, Yale, and PUCP in Lima collaborate on dog genome projects. These studies aim to map out phylogenetic trees, preserving native lineages before they vanish.

Future of South American Dog Breeds

While progress is evident, threats remain: interbreeding, habitat loss, and lack of funding. To secure the future of breeds like the Chiribaya Dog (through cloning or breeding recreation), awareness must grow in both academia and public culture.

Conclusion

Dogs were not just pets in Inca society; they were guardians, companions, and spiritual symbols. Through burials, myths, and modern conservation, these animals continue to shape South America’s living heritage. Their enduring legacy reminds us that to understand a civilization, we must also study the animals they cherished.