Dogs in Ancient and Medieval Art: Symbolism, Representation, and Cultural Meaning

Introduction

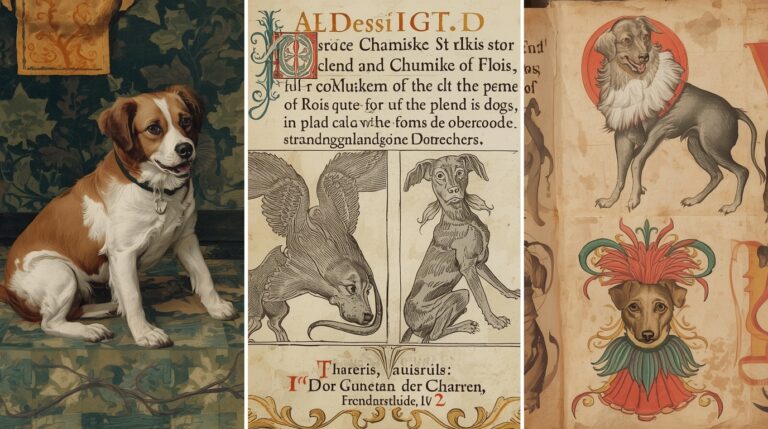

Dogs have accompanied humanity not only in daily life but also in the artistic traditions of nearly every historical period. From Ancient Egyptian tombs to Gothic cathedral stained glass, the image of the dog carried diverse meanings—ranging from loyal guardian to spiritual guide, hunting partner, and courtly companion.

This article explores how dogs were depicted in art across ancient and medieval eras, emphasizing their evolving roles in religion, culture, and social class.

Dogs in Prehistoric and Early Ancient Art

Some of the earliest representations of dogs appear in cave paintings, notably in regions such as Saudi Arabia and Siberia dating as far back as 8,000 BCE. These images often depict dogs hunting alongside humans, suggesting an early recognition of the dog’s value in cooperative survival.

Also read this Cultural Representation of Dogs Through History

Symbolism of Wild Dogs vs. Domesticated Dogs

Wild dog figures typically represent untamed nature, while domesticated dogs symbolized trust and loyalty. These contrasts became more nuanced in later periods like Mesopotamian and Greco-Roman cultures.

Dogs in Ancient Egyptian Art

In Ancient Egypt, dogs played vital roles both practically and spiritually. Breeds like the Tesem and Saluki were prized for their hunting skills.

Role in Religion and Afterlife

Dogs were associated with Anubis, the jackal-headed deity of the underworld. Tomb paintings often included dogs resting at their owner’s feet, implying a connection between dogs and the afterlife journey.

Tomb Paintings and Reliefs

The tomb of Nebamun (c. 1350 BCE) includes frescoes of hunting scenes featuring agile dogs. These dogs were not just decorative but served to communicate status and reverence.

Dogs in Ancient Mesopotamian Art

Assyrian Reliefs and War Dogs

In Assyrian palace reliefs, especially from the reign of Ashurbanipal (7th century BCE), powerful mastiff-like dogs appear assisting in lion hunts—portraying dogs as symbols of strength and discipline.

Guardian Dogs in Temples

Clay statues of dogs were placed at entrances to homes and temples to ward off evil, suggesting an early belief in dogs as protective spirits.

Dogs in Ancient Greek Art

Greek pottery from the 6th–4th centuries BCE showcases dogs in hunting scenes, domestic settings, and mythological contexts.

Mythology and Dogs

The three-headed Cerberus, guardian of the underworld, is perhaps the most iconic mythological dog. Other depictions include the story of Hecuba transformed into a dog, representing grief and transformation.

Pottery and Reliefs

The Greeks used red-figure and black-figure pottery to depict dogs walking, hunting, or sitting calmly beside their masters—projecting domestic harmony and control.

Dogs in Ancient Roman Art

Romans were passionate about pet keeping, and dogs were often included in domestic mosaics, statues, and paintings.

“Cave Canem” Mosaics

The famous mosaic in Pompeii warns visitors to “Beware of the Dog”—a direct expression of a dog’s protective role.

Hunting Dogs and Sculptures

Elite Roman villas frequently included mosaics of dogs chasing deer or boar. Sculptures showed dogs reclining, playing, or attending noblewomen—showing their status as cherished companions.

Dogs in Byzantine Art

In the Byzantine Empire, art took on a heavily symbolic and religious tone.

Christian Symbolism

Dogs often symbolized faithfulness, but occasionally represented paganism when linked to pre-Christian narratives. Some icons portrayed dogs beside shepherd figures, reinforcing themes of guidance and vigilance.

Illuminated Manuscripts

In texts like the Rabbula Gospels, dogs were small but significant figures—sometimes as parts of larger allegorical narratives.

Dogs in Early Medieval Art

Carolingian and Anglo-Saxon Influence

Books such as the Lindisfarne Gospels include stylized dog figures in the margins. Dogs began to appear in legal codices, suggesting a deeper social significance.

Dogs in Romanesque Art

Tympanum and Sculpture

Dogs were carved into Romanesque church tympanums, usually as hunting companions of saints or biblical characters. These dogs represented earthly loyalty and divine service.

Dogs in Gothic Art

The Gothic era brought realism and emotional depth to dog depictions.

Stained Glass and Altarpieces

In churches like Chartres Cathedral, dogs are found in scenes of martyrdom and pilgrimage. Their presence adds symbolic gravity and emotional connection to the stories.

Dogs in Religious Iconography

Dogs served as guardians, protectors, and moral agents in Christian iconography.

St. Roch and the Healing Dog

Saint Roch, the plague saint, is almost always shown with a dog bringing him bread—symbolizing divine aid and loyalty in suffering.

Dogs in Heraldry and Coats of Arms

Noble Symbolism

Dogs, particularly greyhounds and talbots, appeared in heraldic crests, signaling loyalty, vigilance, and aristocracy.

Dogs in Tapestries and Textiles

Tapestries like the Hunt of the Unicorn depict lavish scenes of nobility hunting with dogs, a pastime deeply tied to social status.

Dogs in Illuminated Manuscripts and Marginalia

In the Book of Hours and other religious texts, dogs often appear in the margins as allegorical figures or comic relief.

Dogs and Social Class Representation

The kind of dog depicted often indicated the subject’s class:

- Lapdogs in noble portraits

- Hunting dogs in military and royal imagery

- Strays in peasant illustrations

Dogs in Warfare and Protection

Some manuscripts and murals depict dogs with soldiers, acting as protectors, scouts, and even attackers—a role rarely acknowledged in modern depictions of medieval life.

Artistic Techniques and Styles

The representation of dogs became more anatomically accurate from Byzantine to Gothic periods, indicating improved observational techniques and changing aesthetic values.

Religious Doctrine and Dog Imagery

Though some theologians viewed dogs as unclean, the positive symbolism of loyalty often prevailed. Art reflected this duality, especially in ecclesiastical works.

Dogs and Women in Medieval Art

Dogs in portraits of women symbolized fidelity and domestic virtue, particularly in betrothal scenes.

Renaissance Transition

As Renaissance humanism emerged, dog imagery grew more realistic and affectionate—a direct carryover from late Gothic iconography.

Conclusion

Throughout ancient and medieval art, dogs were never just background figures. They were symbols, protectors, companions, and spiritual guides—roles that reflected evolving human values and beliefs. Their enduring presence across centuries reminds us of their integral place not just in life, but in humanity’s visual and symbolic legacy.