Colonization and Spread of Breeds Globally

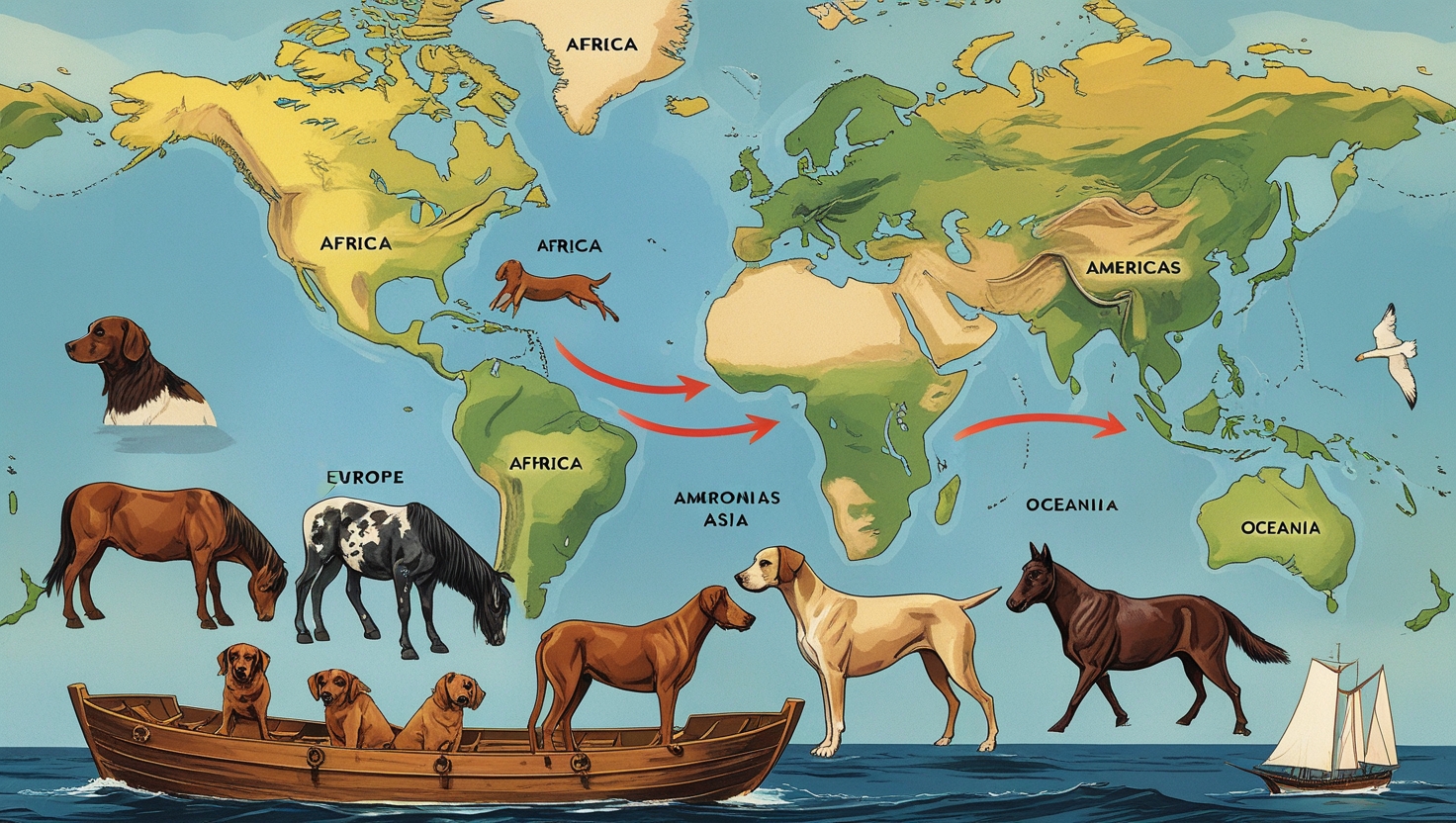

Introduction to Global Breed Movement

The global spread of animal breeds is intricately tied to human migration, colonial expansion, and international trade. As empires expanded, they didn’t just transport goods or people—they brought with them entire ecosystems, including livestock, dogs, horses, and poultry, reshaping the genetic diversity of animals across continents.

The Role of Colonization in Breed Distribution

During the 15th to 20th centuries, European colonial powers such as the British Empire, Spanish Empire, and Dutch East India Company played a pivotal role in introducing non-native breeds to colonized lands. These animals often replaced indigenous breeds, altering both local economies and ecosystems. Colonists imported European cattle, sheep, dogs, and horses to support agriculture, transport, and military needs.

Early Civilizations and Initial Breed Movements

Before modern colonization, ancient civilizations also participated in the movement of animals. The Roman Empire spread cattle and hounds across Europe. The Silk Road facilitated the exchange of camels, sheep, and poultry between Asia and the Middle East. However, these movements were limited in scale compared to the mass breed migrations under European colonization.

The Agricultural Revolution and Domesticated Species

The Neolithic Agricultural Revolution saw the first major spread of domesticated animals, including goats, sheep, and pigs. While this movement was localized, it set the foundation for selective breeding and domestication, practices that colonizers would later implement on a global scale to improve productivity and adaptability of animals in new territories.

Animal Breeds in the Age of Exploration

The Age of Exploration (15th–17th centuries) ushered in a dramatic transcontinental movement of animal species. European explorers carried animals on ships to colonies in the Americas, Africa, and Asia. Spanish conquistadors, for example, introduced Andalusian horses and Iberian pigs to South America, while Portuguese fleets spread European chicken breeds to Southeast Asia and Africa.

Livestock in the British Empire: A Global Dispersal

The British Empire, at its peak, spanned across Asia, Africa, the Americas, and Oceania. With this global presence, the British exported Shorthorn cattle, Merino sheep, Thoroughbred horses, and Terrier dogs to colonies to support agriculture, hunting, and prestige. These breeds often displaced native ones due to their productivity, thereby homogenizing genetic diversity.

Dogs and Horses in Military Colonial Expeditions

Dogs and horses were essential in military conquests. Breeds like the Mastiff, Greyhound, and Collie were employed by colonizers for hunting, guarding, and herding. The Spanish Mustang, for example, became a dominant horse breed in North America, descending from Spanish war horses released or stolen during colonial battles.

Colonial Trade Routes and Genetic Intermixing

The Triangular Trade and Silk Road continuations facilitated the exchange of animal breeds. This led to crossbreeding, such as African goats mixing with European ones, creating hybrids better suited for tropical climates. Similarly, Indian zebu cattle were crossbred with European dairy breeds to improve milk yields in Asia and Africa.

Adaptation of Breeds to New Climates and Terrains

When animals were transported to foreign climates, natural and artificial selection helped shape their evolution. Merino sheep, bred in cool Europe, adapted well to Australia’s dry conditions through selective breeding. European cattle, however, struggled in tropical colonies, leading to the development of hybrid breeds like the Senepol and Brangus.

African Colonization and the Influence on Local Breeds

Colonization in Africa led to the decline of native breeds like the Nguni cattle and Basenji dog, as European breeds were imposed. These native animals were often more resistant to local diseases like trypanosomiasis and more sustainable for local conditions. However, colonial breeding programs prioritized high-yield foreign species, which lacked resilience in African ecosystems.

South American Breeds and Iberian Influence

South America saw an influx of Iberian livestock—Spanish and Portuguese breeds such as the Criollo cattle, Iberian pigs, and Spanish Andalusian horses became foundational in many rural economies. These animals adapted over time, resulting in landrace breeds like the Chilote horse in Chile and Pantaneiro cattle in Brazil.

Southeast Asia’s Hybrid Poultry and Swine Genetics

European colonizers introduced Leghorn chickens, Yorkshire pigs, and goats to Southeast Asia. Over time, these interbred with local breeds, giving rise to hybrid chickens known for both egg-laying and meat. Swine genetics were also modified, creating dual-purpose breeds well suited for tropical environments and smallholder farming.

North America: European Importation of Breeds

North America became a melting pot of animal genetics. Colonists brought Devon cattle, English sheep, and European dogs. Over time, these interbred with escaped or feral animals, producing distinct American breeds like the Carolina Dog, American Quarter Horse, and Texas Longhorn—each influenced by both colonial and native genetics.

Australia’s Sheep Boom and English Breeds

In Australia, colonists introduced Merino sheep, Border Collies, and British Shorthorns, forming the backbone of the Australian wool and meat industries. These breeds flourished in open rangelands, and through selective breeding, Australia developed some of the most productive sheep and cattle lines in the world.

Crossbreeding Practices by Colonial Settlers

Settlers often crossbred indigenous animals with European breeds to improve meat production, milk yield, or working ability. In India, for instance, the native Zebu cattle were crossbred with Holstein Friesians to create dual-purpose breeds. These practices, while beneficial in yield, reduced the genetic purity of native stock.

Genetic Bottlenecks and Breed Homogenization

One consequence of colonial breeding was genetic bottlenecking. With a focus on a few high-performing breeds, diversity declined. For example, the widespread use of British Shorthorn cattle globally led to the displacement of hundreds of local cattle breeds, many of which are now extinct or endangered.

Cultural Implications of Imported vs. Native Breeds

Colonialism not only impacted biodiversity but also cultural heritage. Native breeds often had spiritual, economic, or status value in indigenous communities. The introduction of foreign breeds marginalized these animals, leading to loss of traditional knowledge associated with local animal husbandry practices.

Indigenous Breeds and Their Decline Post-Colonization

Post-colonial periods often witnessed the continued decline of indigenous breeds due to lack of support, modern farming preferences, and market-driven breeding. Many breeds, like India’s Kasaragod Dwarf goat or Africa’s Sheko cattle, are now at risk, with only a few conservation programs in place.

Conservation Movements and Genetic Preservation

Today, breed conservation efforts focus on restoring and preserving the genetic diversity lost during colonization. Organizations like FAO, Rare Breeds Survival Trust (UK), and National Bureau of Animal Genetic Resources (India) are cataloging and protecting native breeds. These efforts are vital in addressing climate adaptability and sustainable farming.

Modern Breeding Techniques vs Colonial Practices

Modern breeding involves genomic selection, cloning, and AI technologies, while colonial breeding was based on visual traits and productivity. Despite technological advances, the ethical and ecological lessons from colonial-era breed dissemination highlight the importance of sustainable genetic diversity over uniformity.

The Role of Breed Associations and Registries

Global associations now maintain stud books, registries, and DNA profiles for breeds. While this began in colonial times to standardize breeds like Jersey cattle and Thoroughbreds, today these associations also work toward recognizing rare native breeds, pushing back against the colonial legacy of homogenization.

Case Study: The Spanish Mustang in the Americas

Descended from horses brought by Spanish colonists, the Spanish Mustang adapted to the North American plains and became the foundation stock for many wild and working horse breeds. Once nearly extinct, dedicated breeders have revived the Mustang through preservation breeding.

Case Study: British Shorthorn Cattle in Oceania

British colonists introduced Shorthorn cattle to New Zealand and Australia in the 1800s. Their fast growth and meat quality made them the standard for decades. However, this led to the decline of smaller, indigenous breeds and environmental strain due to their feed and water demands.

Long-Term Genetic Impact of Colonial Breed Movement

The genetic legacy of colonization is both positive and negative. While some hybrid breeds offer excellent productivity, others have become genetically fragile due to inbreeding. Restoring genetic variety now requires a multi-continental effort, balancing efficiency, resilience, and heritage.

Conclusion: Lessons from History and the Need for Preservation

The colonization and global spread of breeds reshaped the animal genetics of the modern world. While it fueled productivity and economic gain, it also caused homogenization, biodiversity loss, and cultural erosion. Moving forward, conserving indigenous breeds and embracing genetic diversity are essential for ecological stability and sustainable agriculture.

Also read this Dog History by Region