The Role of Dogs in Ancient Greece and Rome

Introduction to Dogs in the Classical World

Dogs played a vital role in both Ancient Greek and Roman societies. They were not only working animals but also spiritual symbols, mythological figures, and companions. Their presence spanned the spectrum from humble homes to majestic temples and battlefields. Whether depicted guarding gates to the underworld or sitting beside aristocrats, dogs served diverse, meaningful functions that shaped the classical world’s understanding of loyalty, guardianship, and animal companionship.

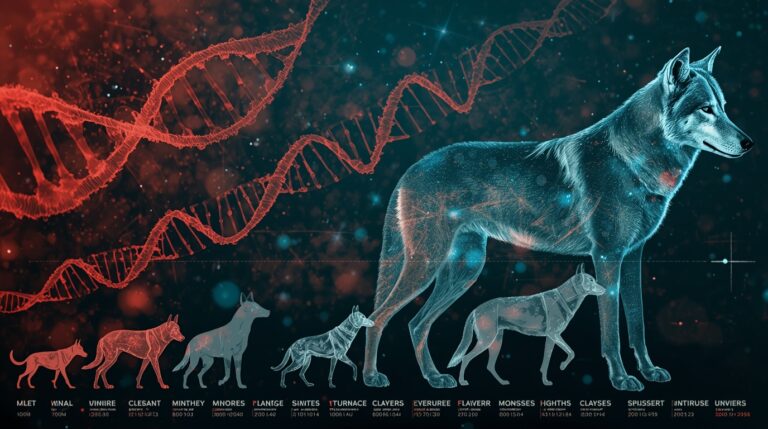

Domestication of Dogs in the Ancient Mediterranean

Dogs were domesticated in the Mediterranean by the second millennium BCE, with evidence pointing to early breeding practices in regions like Mycenae and Crete. The Greeks and Romans inherited a legacy of selective breeding for tasks such as guarding, hunting, herding, and companionship. This focus led to distinct breeds like the powerful Molossian hound and the swift Laconian dog. Dogs were not merely pets—they were shaped into tools for defense, survival, and spiritual significance.

Common Dog Breeds of Ancient Greece

The Molossian Hound, originating from Epirus, was the most famous breed in Ancient Greece. Known for its large size and ferocity, this mastiff-like dog protected livestock from wolves and bandits. Aristotle described it as an intelligent and courageous animal, making it ideal for defense.

In contrast, Laconian and Cretan hounds were bred for speed and agility. These dogs were highly prized for their hunting skills and often depicted in vase paintings chasing game. Their bodies were lean, their noses sharp, and their training precise, making them essential companions for aristocratic hunters.

also write this Dogs in Ancient Civilizations

Roman Dog Breeds and Their Traits

Romans developed their own breeds, such as the Canes Pugnaces, which were war dogs trained to fight alongside soldiers. These canines wore armor, carried supplies, and were deployed in shock tactics during battles. They were particularly effective against cavalry.

Roman villas also housed companion dogs, including early versions of small breeds like the Pomeranian or the Italian Greyhound. These dogs served elite families as lapdogs and status symbols, pampered and adorned with jeweled collars. They were loved for their affectionate nature and refined appearance.

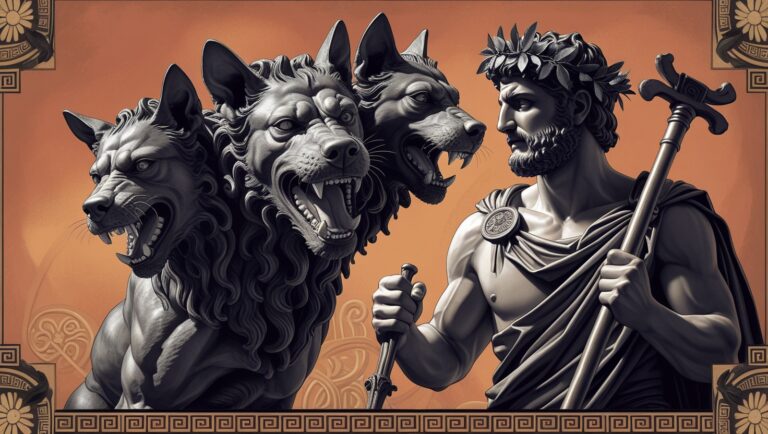

Dogs in Greek Mythology

Greek mythology is rich with canine figures. The most famous is Cerberus, the three-headed dog that guarded the gates of Hades. Cerberus symbolizes the boundary between life and death and loyalty to one’s post. Another mythological dog, Laelaps, was destined never to fail at catching its prey. Given as a gift by Zeus, Laelaps was eventually turned to stone during a paradoxical chase against a fox that could never be caught.

Dogs in myth served as metaphors for divine law, fate, and balance. Their roles were not just symbolic—they were often honored or feared, depending on their mythological alignment.

Dogs in Roman Myth and Legend

Romans held dogs in spiritual esteem, often associating them with omens and sacred rites. Barking dogs were seen as forewarnings of death, while silent dogs in rituals were believed to keep away evil spirits. Some households even kept dogs as protectors of the dead.

In Roman funerary art, dogs are often shown lying beside tombs or following their masters in the afterlife. These images suggest a belief in the eternal loyalty of dogs, extending even beyond death. Certain Roman rites included dog sacrifices to deities like Mars or Hecate, showing their dual role as guardians and offerings.

Symbolism of Dogs in Art and Religion

Dogs appeared prominently in both Greek and Roman religious symbolism. They were sacred to goddesses like Artemis, Hekate, and Diana, each representing aspects of the wilderness, moon, and protection. In temples dedicated to Artemis, dogs would sometimes accompany priestesses in ceremonies.

Art from the period—mosaics, statues, and reliefs—depicted dogs alongside gods and humans, reflecting their spiritual role. For instance, a sculpture of Hekate is often shown with her hound, reinforcing the dog’s role as a guide between worlds.

Dogs as Guardians and Hunters

Greeks often kept dogs to guard property and livestock. A common practice was placing dogs at the entrance of homes to alert owners of intruders. Ancient texts recommend feeding them well and treating them as members of the household, particularly in rural estates.

Romans also valued dogs for hunting and protection. Hunting parties would train dogs to take down wild boars and deer. These dogs worked in packs, guided by hunters who used whistles and signals. Dogs were so critical in these expeditions that some Roman nobles maintained entire kennels staffed with caretakers.

Military Use of Dogs in Ancient Rome

The Romans integrated dogs into their military strategies. War dogs were trained to charge enemies, disrupt cavalry lines, or act as sentries at night camps. They wore armor made from leather or metal and were trained to obey Latin commands.

Pliny the Elder documented their effectiveness, noting that dogs defended soldiers from ambushes and even detected enemies at a distance. These animals were not only tools of war—they were honored with burial rites and inscriptions for their bravery.

Philosophical Views on Dogs

Greek philosophers were fascinated by animals, particularly dogs. Aristotle, in Historia Animalium, analyzed their sensory perception, social behaviors, and intelligence. He praised dogs for their ability to distinguish between friends and strangers, calling them rational creatures in a limited sense.

The Cynic school of philosophy, founded by Antisthenes and carried forward by Diogenes, took its name from the Greek word for dog (kynikos). These philosophers saw the dog as a symbol of natural living, honesty, and disregard for materialism—essential values in their philosophy.

Dogs in Literature and Epic Poetry

In Homer’s Odyssey, the loyal dog Argos is a profound symbol of unwavering faith. After twenty years of waiting for Odysseus, Argos recognizes his master upon his return and dies peacefully. This brief scene encapsulates the themes of loyalty and passage of time.

Roman poets like Virgil referenced dogs in the Aeneid, usually in scenes of hunting or guarding. In Ovid’s Metamorphoses, dogs appear in both tragic and heroic roles. Their literary presence was not decorative—it was emotional and thematic, used to explore loyalty, instinct, and fate.

Canine Imagery in Greek and Roman Art

Canine figures are abundant in mosaics, frescoes, pottery, and statuary. In Pompeii, many homes featured entrance mosaics with the warning “Cave Canem”—“Beware of the Dog.” These signs were functional but also a point of artistic pride.

Vases from Athens often showed scenes of dogs at play, hunting, or beside their masters. Dogs also appeared in funerary art, symbolizing loyalty and transition into the afterlife. Some coins even bore dog images, linking them to military valor and household virtue.

Religious Roles and Sacrificial Ceremonies

Dogs held religious significance beyond mythology. In rituals dedicated to Hekate, black dogs were offered as sacrifices to purify homes and ward off spirits. These ceremonies took place at crossroads, where Hekate was believed to reside.

In Rome, dogs were used in Lupercalia, a fertility festival in which sacrifices were made to Faunus, a god of the wild. Dogs were symbols of primal energy and boundary-crossing, making them ideal participants in rites invoking protection and vitality.

Dogs in Daily Life

Dogs were common companions in urban and rural life. In Greek cities, they accompanied children to the gymnasium or played in the agora. In Rome, they sat beside bathers or followed traders through the forum.

Though their roles differed by class, dogs were everywhere—from palace gates to alleyways. Inscriptions and graffiti reveal names like “Tigris,” “Lucius,” and “Lupa,” showing affection and familiarity.

Veterinary Practices and Animal Care

Ancient sources like Columella, Varro, and Apsyrtus wrote manuals detailing dog health. Topics included treatment for rabies, dislocated joints, and infections. Remedies involved herbs like thyme, vinegar solutions, and even surgical techniques.

Owners also took preventive care seriously. Dogs were groomed, brushed, and fed specific diets depending on their role—meat for hunters, grains for guard dogs. These practices indicate a society that deeply cared for animal well-being.

Funerary Practices and Dog Burials

Graves for dogs have been found throughout Greece and Rome. In Athens, stone markers dedicated to dogs contain emotional epitaphs. One reads: “To Parthenope, who never left my side.”

In Pompeii, skeletons of dogs were found beside their owners, suggesting they perished together during the eruption of Vesuvius. Dogs were often buried with favorite toys or collars, showing their integration into family life.

Women and Dogs in Classical Antiquity

Women of high status often kept small lapdogs as companions. These dogs were seen as symbols of feminine virtue—chastity, loyalty, and grace. In Greek drama, women with dogs were portrayed as gentle and cultured.

Roman women featured their dogs in portraiture, especially in funerary monuments. These dogs were often given poetic names and adorned with fine collars, emphasizing their role in social status.

Dog Collars, Leashes, and Tools

Dog collars in antiquity ranged from simple leather straps to decorated bronze rings with engravings. Wealthy Romans often personalized collars with inscriptions such as “I belong to Marcus, bring me home if lost.”

Leashes made from flax or linen were used for control in urban areas. Some dogs wore harnesses with bells to alert owners of movement. These artifacts reveal the complexity of canine equipment in classical life.

Dogs and Slaves: Socioeconomic Symbolism

In both cultures, dog ownership reflected social standing. Wealthy families owned decorative or purebred dogs, while lower classes and slaves worked with dogs used for labor. The presence of a dog in art often indicated the status of the owner.

In literature, slaves and dogs are sometimes compared—both loyal but subservient. However, many stories show dogs treated better than some servants, hinting at the value Romans and Greeks placed on canine loyalty.

Legacy of Ancient Canine Culture

Many modern dog breeds trace their lineage to these classical dogs. The Neapolitan Mastiff, for example, is believed to descend from the Molossian hound. The reverence for dogs in storytelling continues today, with figures like Cerberus appearing in video games, films, and literature.

The values that Greeks and Romans saw in dogs—fidelity, protection, courage—remain timeless. Their writings, art, and mythology serve as cultural proof of the dog’s deep and unshakable role in human society.