Dogs in Ancient Egypt (Deities, Burials, Hunting)

Introduction: Dogs as Sacred and Functional Beings

In ancient Egyptian civilization, few animals held as diverse and profound a role as the domesticated dog. Revered as divine guardians, cherished as pets, and deployed as hunting companions, dogs appeared across multiple layers of religion, art, and daily life. Their presence in temple offerings, tomb inscriptions, and funerary rituals illustrates a deep emotional and spiritual connection between ancient Egyptians and their canine companions. This article explores the multifaceted role of dogs in Ancient Egypt, with a focus on their influence in mythology, burials, and hunting traditions.

Read more about Origins and Domestication of Dogs

Canines in Ancient Egyptian Society

Dogs were integrated into urban households, temple complexes, and royal hunting parties. They were not simply animals of utility but companions imbued with protective, magical, and symbolic qualities. As early as the Old Kingdom (~2686–2181 BCE), evidence shows that dogs lived with humans in both elite and commoner contexts. They featured in household inventories, funerary reliefs, and pet names were often inscribed on tomb walls.

Dogs in Egyptian Mythology and Religion

The spiritual landscape of ancient Egypt included a pantheon of zoomorphic deities, many of which were associated with death and the afterlife. Among these, the most prominent canine figure was Anubis, the jackal-headed god of mummification and the afterlife. Dogs were considered liminal animals—creatures that traversed both the living world and the realm of the dead. This dual identity made them essential in religious iconography and ritual.

The Role of Anubis: Protector of the Dead

Anubis (Inpu) was worshipped as the guardian of cemeteries and embalming chambers. Often depicted as a black jackal or a man with a jackal’s head, Anubis was believed to oversee the weighing of the heart in the Hall of Judgment. His dark coloration symbolized both fertility and decay—the cycle of death and rebirth. Archaeological evidence links Anubis worship with the presence of dog burials and temple dog sanctuaries across necropolises such as Saqqara.

Wepwawet: The Opener of Ways

Another canid deity, Wepwawet, also featured heavily in military and funerary contexts. Known as the “Opener of the Ways”, Wepwawet was believed to guide the deceased through the treacherous paths of the Duat (Egyptian underworld). Unlike Anubis, who was associated with the internal preparation of the body, Wepwawet symbolized protection during passage—an ancient equivalent of a psychopomp.

Jackal Symbolism in Death and Rebirth

Jackals were closely tied to the desert cemeteries where many Egyptians were buried. Scavenging jackals that prowled burial grounds likely inspired the mythical transformation of these animals into protective deities. In many cases, the lines between jackal, dog, and hyena blurred in religious texts, reinforcing their role as watchers at the threshold of life and death.

The Cult of Dogs in Cynopolis

The ancient city of Cynopolis, meaning “City of Dogs,” was located in Upper Egypt and served as a major cult center for Anubis worship. Here, dogs were venerated, housed in temple sanctuaries, and upon death, mummified and buried ceremoniously. Excavations at Cynopolis reveal dedicated cemeteries filled with canine remains, indicating a special status akin to sacred animals like cats and ibises.

Dogs as Temple Animals and Guardians

In many temple precincts, dogs were considered guardians of sacred space. Temple inscriptions describe dogs that were fed, named, and housed by priests. Inscriptions in the Temple of Seti I refer to dogs that “walk beside the gods” and act as “servants of Anubis.” Their symbolic presence added layers of protection and spiritual authority to temple ceremonies.

Saqqara: Mass Dog Burials Near Anubis Temples

The necropolis of Saqqara, one of Egypt’s most sacred funerary zones, yielded thousands of mummified dog remains. Discovered near Anubis’s temple, these burials date back to the Late Period (664–332 BCE). The mummies vary in preservation, suggesting both ritual offerings and the sacrificial breeding of dogs for temple economies. Some animals appear to have been reverently buried, while others were mass-produced offerings, raising ethical questions about ancient animal cult practices.

Mummification of Dogs for Ritual Purposes

Dog mummification was a significant religious practice, believed to:

- Honor Anubis

- Protect tombs

- Serve as votive offerings

Techniques ranged from resin embalming to linen wrapping and even gilding in elite cases. X-rays and CT scans of dog mummies have revealed their age, health status, and even causes of death, offering valuable insights into ritual animal treatment.

Dog Cemeteries and Temple Offerings

In addition to Saqqara and Cynopolis, Asyut and the Theban necropolis have yielded dog cemeteries. Some tombs include stelae and inscriptions, such as “Beloved of Anubis” or “Guardian of the House.” These inscriptions support the idea that dogs held religious roles, not just as pets but as agents of divine will.

Artistic Depictions of Dogs in Tombs

Dogs are frequently depicted in tomb paintings, particularly in hunting scenes or banquets. These images provide clues about ancient Egyptian dog breeds, their roles in society, and how they were perceived aesthetically. Dogs are shown with collars, indicating domestication, and are often painted with distinct color patterns, such as red coats with white spots.

Tomb Paintings: Hunting Dogs with Pharaohs

In royal tombs, such as those of Tutankhamun, Amenhotep II, and Thutmose III, dogs are seen assisting in desert hunts for hares, gazelles, and lions. These royal hunting expeditions were not merely sport but expressions of dominion and cosmic order. Dogs helped maintain ma’at (balance) by eliminating chaos symbolized by wild animals.

Breeds of Ancient Egyptian Dogs

While not classified in modern taxonomic terms, Egyptian art suggests the presence of:

- Greyhound-like hounds: tall, slender, speed-oriented

- Saluki-type dogs: loyal and graceful

- Mastiff-type dogs: robust guardians

- Short-legged terriers: possibly used for vermin control

These ancient Egyptian dog breeds served specific roles and were sometimes crossbred to enhance traits.

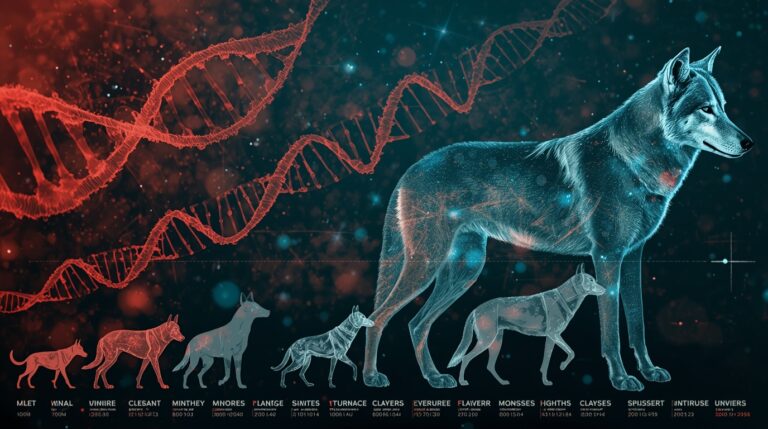

Physical Characteristics: Greyhound-like and Mastiff-types

From New Kingdom art and animal osteology, scientists infer dogs with:

- Deep chests and long limbs (hunting)

- Broad skulls and muscular bodies (guarding)

- Pricked ears or drooping ears

- Short coats, suitable for the desert climate

Skulls recovered from tombs show variations linked to selective breeding by social class and occupation.

Dogs in Hunting: Royal Desert Expeditions

Dogs were essential for tracking, chasing, and retrieving prey. Often working in packs, they were trained to hunt:

- Deer

- Ibex

- Oryx

- Wild fowl

Paintings in the Tomb of Nebamun show dogs working in tandem with hunters and falconers, reinforcing their intelligence and obedience.

Functional Roles: Guarding, Tracking, Protecting

Beyond hunting and religion, dogs served practical functions:

- Guard dogs in estates and temples

- Tracking animals for soldiers and law enforcers

- Personal protectors for children and elite women

Some funerary texts describe dogs that “never left their master’s side,” emphasizing their loyalty.

Dogs as Pets in Noble and Common Households

Archaeological and textual evidence shows that dogs were kept as household pets. Tombs contain painted collars, inscriptions, and even dog names, such as:

- “Abuwtiyuw” (one of the oldest named dogs in history)

- “The Faithful”

- “The Silent One”

Some dogs were buried in individual tombs, suggesting deep emotional bonds.

Emotional Bonds: Naming and Pet Tomb Inscriptions

Inscriptions from elite tombs often read:

- “He who was buried like a man”

- “My loyal companion, who protected me at night”

Such texts demonstrate that ancient Egyptians anthropomorphized their dogs, valuing them not just functionally, but emotionally and spiritually.

Animal Cults and Ceremonial Animal Worship

Dogs were part of broader animal cults that included cats (Bastet), ibises (Thoth), and crocodiles (Sobek). In temple economies, dogs were:

- Raised specifically for ritual slaughter

- Buried in mass cemeteries

- Embalmed for sale to pilgrims

This blend of sacrifice, commerce, and worship reflects the complex cultural economy around sacred animals.

Cultural Syncretism: Dogs and Hybrid Deities

As Egyptian religion evolved and absorbed elements from Nubia, Persia, and Greece, canine figures like Anubis merged with other deities:

- Hermanubis (Anubis + Hermes) during the Hellenistic period

- Similarities with Cerberus, Hecate’s hounds, and Zoroastrian Sagdid rituals

These transformations show how dogs in Egyptian religion transcended borders and persisted into late antiquity.

Osteological Evidence from Archaeological Sites

Animal osteology helps confirm:

- Age at death

- Signs of trauma or disease

- Breeding patterns

Remains from Saqqara, Thebes, and Cynopolis show that temple dogs often lived short lives, suggesting mass-rearing practices, while elite pets showed long-term care and grooming.

Museums and Collections: Legacy of Egyptian Dogs

Dog artifacts can be found in:

- Louvre Museum – Egyptian Antiquities

- British Museum

- Museum of Cairo

- Metropolitan Museum of Art

These include dog statues, painted ceramics, mummified remains, and temple carvings, all of which confirm the widespread cultural impact of dogs.

Modern Interpretations of Dog Symbolism in Egypt

Today, scholars reinterpret dog symbolism in Egypt through lenses of:

- Gender studies

- Posthumanism

- Animal agency theory

They argue that dogs weren’t just passive beings, but active participants in ritual, politics, and personal life.

Conclusion: Legacy of Dogs in Egyptian Culture

Dogs were not marginal figures in ancient Egyptian life—they were sacred, symbolic, and social actors. From divine guardians like Anubis to hunting partners of pharaohs, and from beloved pets to ritual offerings, they left paw prints across the religious and cultural landscape of ancient Egypt. Their roles reflect a civilization that valued animals not only for utility but also for their emotional and spiritual resonance—a legacy that continues to fascinate scholars and animal lovers alike.